|

|

Lee's Adventures on Semester at Sea ® SOUTH AFRICA

|

||

|

Introduction

|

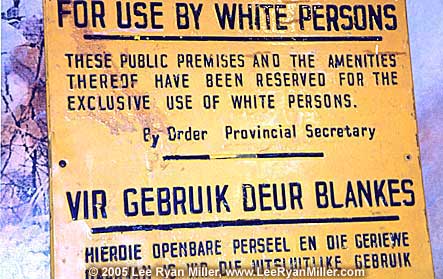

These groups have a history of bloody conflict with one another, and political divisions remain to this day. For example, Coloureds and Asians fear domination by the black majority, and most vote for the Afrikaner-dominated National Party—despite the fact that this party was responsible for the racist system of Apartheid. Most blacks, in contrast, support the African National Congress (ANC). But blacks of the Zulu ethnic group tend to shun the ANC, supporting instead the Inkatha Freedom Party. Afrikaners still mistrust English-speaking whites, a legacy of the brutal Boer War, and resent their economic dominance. As a result, whites are divided among different political parties. Journal entry, February 20, 2003 After we arrived in Cape Town yesterday morning, I boarded a motorcoach and traveled far into the interior of the country to visit the Kagga Kamma game preserve. I was one of the trip leaders. Our guide was Inge Hugo, and our driver was named Pieter. On the long drive, I felt like I had been transported back to California. Iceplants were everywhere (they are, in fact, native to South Africa). Near the city, we passed through an agricultural region that looked like Oxnard. Most of the farmers were white, and those who labored for them had dark skins (Coloureds, in this case, rather than Mexicans). We crossed a mountain range that looked remarkably like the Santa Monica Mountains in southern California. We passed signs along the road for Ceres, Porterville, and Fresno. Gradually, the terrain became more arid, and we saw ostriches running free in a landscape dominated by what looked like sagebrush and wind-carved sandstone sculptures. We arrived at Kagga Kamma at lunchtime. The “gg” in the name of the park was pronounced by Inge like the “ch” in German (or the sound you make when you clear your throat). Inge spoke Afrikaans, English, and German fluently. She told us that Kagga Kamma means something like “beautiful water” in San, the language of the Bushmen. The park landscape was breathtaking. There were wind-carved red sandstone sculptures that reminded me of Red Rock Canyon near Las Vegas. The other bus transported the people slated to stay in the lodge. Their accommodations consisted of huts or caves. I never saw the inside of these places, but I was told by the students and faculty who stayed there that they were luxuriously-furnished. The people on our bus were slated to stay in the “chalets.” These were not alpine houses like in Switzerland. They were 3-bedroom condos about a mile from the “lodge” area, complete with a kitchen and a living room. We never got an opportunity to use those amenities. But we did take a swim in the pool. Beside it were ancient rock paintings.

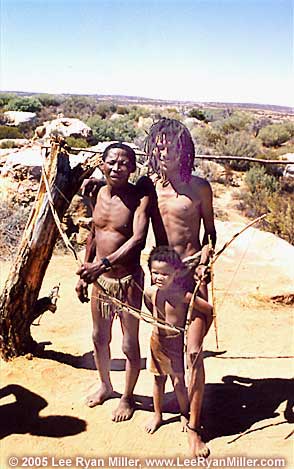

Late in the afternoon, Daan, the ranger, took us for a hike. He sent jeeps to pick us up at our chalets, and we assembled at the lodge. Daan told us a little about the park. Kagga Kamma is a private game preserve. When the land was purchased several years ago, very little wildlife remained. The native animals had been killed or driven off during the past century. So had the Bushmen who had inhabited the region. It had been used as a sheep ranch. The new owners of Kagga Kamma reintroduced native animals like antelope and zebra, and allowed some of the Bushmen to return. They also built the accommodations that we were staying in. We hiked a few miles to the boundary of the park. We exited the gate and walked a short way to the edge of a deep canyon. The drop to the bottom must have been hundreds of feet. Not as big as the Grand Canyon, but a great view nonetheless. We watched the sunset there. Then the jeeps picked us up and brought us back for dinner. Dinner was buffet style, as had been lunch. I particularly enjoyed the salads. The salads aboard ship consisted of iceberg lettuce, tomato and cucumber. Very monotonous. Some of the students said that the ostrich meat was good, but as a vegetarian, I was not interested in trying it. After dinner, we divided into two groups. Pat, the other trip leader, went with one group for the night game drive. I stayed with the other group to look at the stars with an astronomer. The air was extremely clear in Kagga Kamma, there were no city lights anywhere nearby, and the moon had yet to rise. The stars were incredible. I’d never seen so many before. The astronomer allowed us to get a closer view of various planets and constellations with his telescope. Around 11 p.m. the first group returned and we climbed into the jeeps for a game drive. It was getting quite cold. It must have been in the forties. That was a big change from the daytime temperature, which had exceeded ninety degrees. All I had to keep warm was a sweatshirt. Zizi Geller, another professor, lent me a sweater. But the open-top jeep was very cold nevertheless. We located the animals by shining a spotlight out into the bush as we drove along dirt roads. The animals’ eyes would shine. We saw several species of antelope (this “-bok” and that “-bok”—I don’t remember the names), plus a donkey. We saw another set of eyes near the donkey. Daan said that it was a zebra. He explained that a zebra tends to hang out with the donkey. Sounded weird to me. I was an ice cube by the time we got back to the chalets around midnight. Early the next morning the jeeps picked us up. After breakfast, Daan took us on a walk to look at the ancient Bushmen rock paintings in the area. Most were pretty rudimentary drawings of people and animals painted in ochre. Daan said that some were six thousand years old. We had the opportunity to meet a family of Bushmen (San) before we boarded the bus for departure. They were small people with dark brown skins, wearing loincloths. They were in a grass hut. Daan explained that they no longer dressed like this normally—that they had done this for us. The San sold us some handicrafts and then we climbed into the motorcoach. Before we drove off, we saw the San walking past us in modern clothing. The little boy had his loincloth on his head like a hat. As the coach drove out of the park, we saw the donkey again. Daan had not been joking the previous night about the donkey’s favorite companion. Next to the donkey was standing a zebra.

On the drive back to the ship I had the opportunity to chat with Inge, our guide. She was an Afrikaner, but she had surprisingly liberal views. She felt that Apartheid had been very unjust, and she was pleased that it had come to an end. On the other hand, she was quite critical of the current government. She was a schoolteacher by trade, and worked as a tour guide only part-time. She told me that after the end of Apartheid, the government had discovered that there were too many public schoolteachers. So they had announced that they would involuntarily transfer teachers from schools with too many teachers to other schools that were in need of more teachers. If teachers wished to avoid involuntary transfer to a school not of their choosing (probably one of the worst schools, many teachers feared), the government offered them a lump sum payment of two years’ salary to resign their positions. Large numbers of teachers accepted this lump-sum payment, according to Inge, and either left the teaching profession, or went to work in private schools, or emigrated to another country that was hiring teachers. To the misfortune of the government, they neglected to place limits on the number of teachers per discipline who were permitted to leave the profession. As a result, South Africa went from having too many teachers overall, to having a severe shortage of math and science teachers. In response, the government proposed importing math and science teachers from Cuba. This met with public outcry, according to Inge, and they instead decided to train new math and science teachers. I asked why they hadn’t just hired back some of the experienced teachers who had left, and Inge just shrugged her shoulders. (Inge was a foreign language teacher. She had accepted the lump sum and moved to a private school).

Inge also was critical of the government’s handling of the economy. She said that she believes that Apartheid was unjust, and that she has Coloured friends, but that it is now very hard for middle class whites to make ends meet. Prices, she explained, had not kept up with wages. I refrained from asking her how blacks in the townships were faring if middle class whites were having difficulty. The townships are the poor shantytowns ringing Cape Town and other South African cities, where poor blacks and Coloureds live. On the way back to the ship, we stopped at Worcester (pronounced “Vooster” in Afrikaans), a town in the wine-producing region north of Cape Town. We visited a museum recreating life in Dutch colonial times three centuries ago, and then did some wine tasting at a wine institution funded by several local wineries. Then we returned to the ship around 6 p.m. As I walked up the gangway, Jessica, one of the ship’s nurses, asked me if I had plans for the evening. I said no, and she suggested that we take the aerial tram up to the top of Table Mountain to watch the sunset. We did so, and had a lovely view of the city. Afterwards, we had dinner at the Africa Café, a restaurant recommended by Inge. The restaurant was located in a 150-year-old house in downtown Cape Town. Each of the rooms had been brightly painted to represent the culture of a different African country. The staff were dressed in colorful clothing, and periodically a group of women would stop what they were doing and make their way from room to room, singing and dancing in their native language. When we inquired of one woman what language they were using, her reply was a clicking sound followed by what sounded like “ho-sa.” Jessica begged her pardon, and she repeated the same sounds. She explained that it was written Xhosa, and that the “x” represents the clicking sound. She said that it was a common native language in this region of the country. Then she gave us a run-down of various clicking sounds in the language, and the letters that they use to represent these sounds. Fascinating. The food was excellent, inexpensive, and much too plentiful. They charged you per person, rather than per dish, and brought you a dozen different dishes, each from a different country. All but three were vegetarian. We could only finish half of the food brought to us. Including drinks, the bill came to only about $30. We got back to the ship very late. Journal entry, February 21, 2003 I slept late, and left the ship in time for lunch. I found a restaurant in the port area and had a pizza. Nice change from the monotony of the shipboard food. Our ship docked at the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront. Just beyond the gangway lay a huge indoor/outdoor shopping mall, as nice as any of the fanciest malls I have seen in the U.S. Not unlike an upscale American shopping mall, most of the shoppers were middle class and rich white people. Blacks and Coloureds mostly were doing low-skilled work, like manual labor, food service, and security. For example, in the restaurant, the patrons were all white, the waiters were white, and the bus boys were black or Coloured. Now that I think about it, it is not hard to find situations like that in parts of the US. Interesting how one notices such things more while abroad. I asked the security guard in the indoor portion of the mall for an electronics shop. The antenna had broken off my short-wave radio shortly after we left Nassau, and I was hoping to tune into the BBC World Service for news. The security guard took me to a couple of stores, but they could not help me. So he took me to a couple of electricians on staff at the mall. They attached some wire in lieu of an antenna. I gave the two electricians and the security guards each a tip. Then I walked to downtown Cape Town. I walked to downtown Cape Town one day. It must have been a couple of miles, and gave me an interesting perspective on life in urban South Africa. The city looked clean and prosperous. By the waterfront were lots of new, modern shops and condos. Downtown Cape Town was a mixture of modern and older architectural styles. But I saw no crumbling buildings, and few signs of poverty. This stood in stark contrast to the townships on the outskirts of the city, which I will describe later. While downtown, I visited the District Six museum. District Six was formerly a mixed-race neighborhood in Cape Town. Apartheid was only adopted as official government policy after 1948, and the segregation of neighborhoods was not completed until the late 1960s. District Six was one of the last neighborhoods to be segregated. The Apartheid-era government had decreed that the cities would be all-white, and made the non-whites move to the townships ringing the cities. The residents of District Six demonstrated and protested, but to no avail. They were expelled, and their neighborhood was bulldozed. The government tore down all buildings besides churches. The former residents, however, continued protesting, and no developer was willing to build in the neighborhood. The only new structure ever built was a college that the government built on a small portion of the vacant land. Today, the college and some churches are the only structures still standing in District Six. It is an eerie ghost town surrounded by a bustling city. The museum was excellent. It was small, but it gave you a good sense of the rich community life in District Six before its demolition, the protests against its destruction, and the impact of this event on the lives of its former residents. The museum has been funded with grants from groups in the U.S. and Europe. The docent I spoke to on my visit was a former resident of District Six, and his first-hand accounts of its history greatly enriched my understanding of this microcosm of South African history. Apartheid was dismantled in the early 1990s, and the first black-majority government was elected in 1994. Recently, the government has decided to allow the former District Six residents to return, and is giving them money to build homes on the sites that they formerly occupied. It remains unclear what will be done for those whose sites are now occupied by the college. After exiting the museum, I strolled through the park adjacent to Parliament and the various museums. Then I took a taxi back to the ship. I had dinner with Kevin Murphy (history professor) and Brandon Som (English professor) in the port area. I went to bed at a reasonable hour, since I was scheduled to depart early the next morning on a visit to some townships. Excerpt from an article I wrote for Stanislaus Connections In last month’s installment, I described Cape Town, South Africa, a modern, First World city that has much in common with cities in the United States. On February 22, 2003, I led a group of students on a trip to visit the Third World. We did not have to travel far. We only had to travel to the outskirts of Cape Town. We spent the day as volunteers for Operation Hunger, a non-governmental organization that focuses on alleviating hunger and malnutrition in South Africa. Our guide was Clement, a former preacher from the region to the north of Cape Town, who is now the coordinator of Operation Hunger for the Western Cape Province.

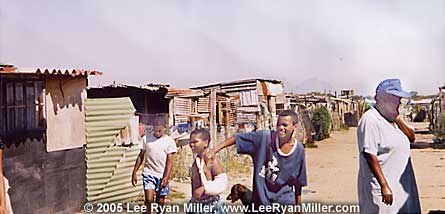

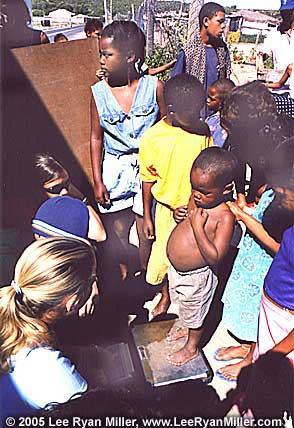

In the morning we traveled by chartered motorcoach to Chris Hani Park, a township on the outskirts of Cape Town. “Township” is the name South Africans give to the settlements that millions of destitute people build on the outskirts of cities. Our task was to weigh the children living there in order to assess the scope of malnutrition. Clement explained that with our help, he would accomplish in a couple of hours a task that would take him weeks on his own. We brought along toys, pens, coloring books, and other items to give out to the kids. Clement brought packets of instant soup. As soon as we arrived, a crowd gathered around our coach. Since it was Saturday, most adults were at home. Clement told us that we would work only until lunchtime. There is a lot of alcohol abuse in the townships, he explained, and the local people would likely be drunk and uncooperative in the afternoon. The community we were visiting was composed primarily of Afrikaans-speaking Coloureds (descendants of children fathered by Dutch settlers and native women centuries ago), although there were some black families. Despite the fact that there was a mosque across the street from the community, there was only one Muslim family. The rest were Christians. The children formed a line, and a local woman served as a translator. We weighed each child, and recorded his/her age in months. This permitted us to graph the age/weight ratio of the children in the community, and to compare our statistics with what would be normal. We weighted more than one hundred children that morning, and we found that many of them were significantly underweight. After weighing each child, we gave him/her items like coloring books, crayons, pens, and instant soup packages. There were several dozen of us too many for the tasks at hand, so surplus volunteers played with the kids and talked with their parents. There were a number of adults there who spoke English. The children and parents alike requested that we take their photos and send them copies. They were so poor that hardly any families had any photos. The community, Chris Hani Park, was named after the (assassinated) leader of the youth group of the African National Congress (ANC). The ANC is the organization that fought for decades against Apartheid, under the leadership of Nelson Mandela. The ANC is now the dominant political party in South Africa (it has nearly two-thirds of the seats in Parliament). Most of the people living in this township, Clement explained, were supporters of the National Party, not the ANC. The National Party, ironically, was the party of the Afrikaners under the period of white minority rule, and was the architect of Apartheid. The first election under universal suffrage occurred in 1994, and most Coloureds voted for the National Party, for fear that they would face discrimination under a government dominated by the mostly-black ANC. But the people in the township we visited, according to Clement, “saw which way the wind was blowing,” and named their community after the martyred Chris Hani.

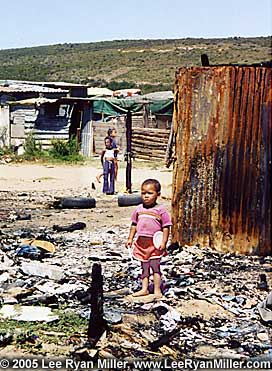

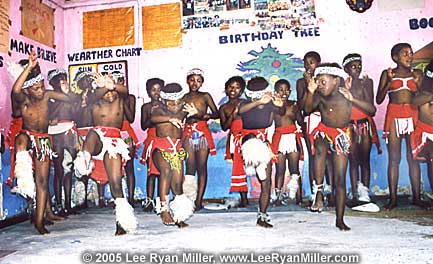

Living conditions in this township were shocking. Families lived in shacks that they constructed out of scrap wood, with roofs made out of metal or plastic tarps. They had no running water, electricity, or sewage. Fires are common, and often burn down several houses before bucket brigades can bring them under control. Clement led us on a tour of the neighborhood. There were some two hundred houses in Chris Hani, situated along narrow dirt roads. There were about five taps on the street from which the residents could draw water for drinking, cooking, washing, etc. It was common for people to drink directly from the taps, or to wash items like dirty diapers below the taps. They did this while standing barefoot in the mud created by the splashing water. Needless to say, disease was a problem in the township. Many families had a few small electric appliances like a lamp or stereo that they hooked up to a car battery for power. Toilets were nonexistent. People built flimsy outhouses to provide privacy as they used buckets. The local government empties the buckets periodically. Aside from the faucets on the street, this was the only service the community received. Presumably the local government emptied the outhouse buckets in order to lessen the likelihood of epidemics. Six months prior, local government officials had forced all the residents of Chris Hani to dismantle their homes and to move across the street. The officials explained that they were planning to build them permanent houses on the old site. Sadly, after the families disassembled their shacks and moved them to the new location, no houses were built at the old location. Months went by, and at the time of my visit, the residents of Chris Hani had just been told that the houses will indeed be built—but that they will be for other people, not them. Adjacent to Chris Hani lay neighborhoods of modest houses—permanent structures, not wooden shacks like those in Chris Hani. Clement explained the difference between the residents of the different neighborhoods: the permanent houses were the homes of people who earn modest but regular incomes. They can afford to pay monthly rent or mortgage payments. The people living in the shacks, in contrast, work whenever they can (seasonally, part-time, etc.) but do not usually receive regular paychecks. Therefore, they cannot afford to move into permanent housing. We left Chris Hani after noon and ate lunch at a rest stop along the highway. Most of us ate only part of our lunch and saved the rest to give to people at our next destination. Excerpt from an article I wrote for Stanislaus Connections This month I begin with our visit to Site C, the largest township around Cape Town. We visited a local community center to attend a dance performance by a group of girls. This dance troop was quite famous, and had performed for former President Nelson Mandela, as well as current president Thabo Mbeki. Girls in the community, we were told, are frequent victims of sexual abuse after school. Women in the community had created the dance troop so that the girls would have someplace safe to go after school. The girls in the troop ranged in age from around 8 to 16 and were dressed in traditional African costumes. They had made rattles out of strings of crushed soda cans, which each girl had tied around one of her ankles. They danced as one girl beat a drum and an older woman sang. Most of the girls were topless. Clement explained that, traditionally, girls do not wear tops until age 18, but that some parents are now requiring their daughters to wear tops—in the hopes of making rape less likely. In South Africa, rape often is a death sentence. Around one-quarter of the population is HIV positive. Life expectancy in South Africa averaged 56.7 years during the late 1990s. It is expected to fall to around 40 within the next five years, due to the AIDS epidemic. Very few HIV-positive South Africans can afford prescription medication to treat their condition, and few live long after they begin showing symptoms of the disease.

After the dance performance, we drove through the commercial section of the township. There were shacks selling all sorts of items, like food and clothing, and others where you could get car batteries charged. (Many township residents, lacking electricity, power small appliances with car batteries.) We visited the shack of a traditional healer. The shack was disordered and quite dirty. He had bunches of all sorts of herbs hanging from the ceiling, bottles of various types of spirits on shelves. The healer claimed that he was able to cure AIDS. He said that, unlike Western drugs, his treatment was affordable to ordinary South Africans. But he cautioned that the treatment was very harsh (causing lots of vomiting and diarrhea), and that many people were unwilling to continue treatment until they were cured. Next we traveled a short distance to a Rastafarian community. It was named after the Jamaican-born black nationalist and social reformer, Marcus Garvey. Our visit to this community presented a refreshing contrast with the sad places we’d visited earlier in the day. This community seemed to be a bit better off economically. People lived in permanent houses, rather than shacks. They wore clothing in good condition, and everyone was smiling. South African townships are dangerous, and a Semester at Sea student had been mugged on a township visit the previous day. But I felt safe in Marcus Garvey. Clement, our guide, who had repeatedly warned everyone not to stray from the group during our previous stops, confirmed that Marcus Garvey was quite safe. He said that there was very little crime in Marcus Garvey, and that when someone commits a crime there, community leaders sit down with the wrongdoer and talk to him about what he had done and why it was wrong. I felt like I had entered a hippie commune. The residents put on a reggae/hip hop concert for us. They had a microphone and loudspeakers. I asked Clement about their relative affluence. He said that not long ago, the community had been very poor and had lived in the bush. Then, as the townships expanded toward their community, the government had built them houses. Clement explained that the residents of Marcus Garvey now grew their own organic food, and remained very community-oriented. “If you have a loaf of bread,” Clement explained, “you make sure to give some of it to your neighbors.” He said that they make money by producing arts and crafts and selling them in the city. Before we left, they offered some of their work for sale to us. No hard sell here. If you were interested, that was okay; if not, that was okay as well. Clement explained that children in this community don’t go to school. The parents won’t allow it, fearing that their unique culture will be disrupted. They are trying to raise funds from Jamaica to establish their own schools. The kids were extremely well-behaved, constantly smiling, and always wanted to hold our hands. Clement also explained that although marijuana is illegal in South Africa, the authorities do not enforce the law in Marcus Garvey. Residents are permitted to smoke ganja weed—as is required by their religion—as long as they don’t smoke it or sell it outside the community. For our benefit, no one was smoking ganja weed during our visit. At the crafts fair they held for us, one man asked me if I’d like to buy some ganja. But when I explained that it was not permitted on the ship, he nodded his head, smiled, and said he understood. South Africa is a beautiful country, rich in culture and natural resources. But it is also beset by serious economic problems, a horrifying AIDS crisis, and an epidemic of violent crime. I pray that South Africans of all races and classes will someday soon be able to put aside their differences and work toward a brighter future. Journal entry, February 22, 2003 We were back to the ship from the Operation Hunger field trip by around 6 p.m. I grabbed some dinner at a restaurant in the port area. Afterwards, a choir from one of the townships joined our shipboard choir to give a concert in the Union. The music was wonderful. Following the concert, we set sail for Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

HOME | ABOUT DR. MILLER | POPULAR WORKS | SCHOLARLY WORKS | APPEARANCES | SEMESTER AT SEA | PHOTOS | CONTACT LEE |

|

|

|

Copyright ©

1998 - 2009 Lee Ryan Miller |