|

|

Lee's Adventures on Semester at Sea ® HAVANA, CUBA

|

||

|

Introduction

|

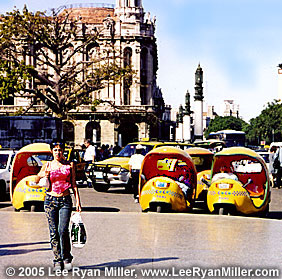

The further we walked from the terminal, the more decrepit the buildings looked. Outside the tourist district, hardly any of the buildings in Havana have been renovated since the revolution, half a century ago. I marveled at the cars. There were large numbers of vintage 1950s American cars. I told Ransel that Cuba must have the best mechanics in the world. I could not believe that these cars were still running. This is all the more remarkable, given that Cuba has not been able to import spare parts for these vehicles for over forty years, due to the U.S. trade embargo. In addition to the classic American cars, there were many boxy Soviet-era vehicles. Ransel explained that the government tries very hard to keep locals separated from foreigners. Locals are not allowed to use the tourist taxis, and foreigners are not allowed to take the public transportation. Goods and services meant for locals are cheap and scarce. Goods and services meant for tourists are plentiful and expensive. The whole point of the tourist industry, Ransel explained, is for the government to collect as many dollars as possible.

Ransel cautioned that we needed to be discrete. The government does not permit social interaction between locals and foreigners. At any point, he said, the police might stop us and arrest him. I started glancing worriedly around police officers. Ransel laughed. "Don't worry. They probably won't bother us, as long as we are not too obvious." He explained that the rule tends to be enforced only sporadically, and that they mostly go after locals who try to take advantage of tourists, like con artists and prostitutes. We walked until we reached the Capitola, a building apparently modeled after the US Capitol in Washington, DC. In front of it were statues of various historic figures from Cuban history. In a park across the street were statues of various foreign historic figures, including, to my surprise, Abraham Lincoln. At this point Ransel asked me to put my camera away and to keep quiet, so that people would not know I was a foreigner. I complied and he hailed a cab. This was one of the old, beat-up cabs that the locals use. We both sat in the front seat. I sat silently as we drove quite a distance into central Havana. The cab stopped a couple of times to take on additional passengers. Ransel later explained to me that such cabs follow a prescribed route, taking on and letting off passengers along the way. The architecture was breathtaking. There were buildings with wrought iron balconies like in the French Quarter of New Orleans. There were neo-classical buildings with columns in front. There were art deco buildings. A few were painted bright colors. Most look like they once had been painted as such, but now only a bit of peeling paint clung to them. Most buildings, in fact, appeared to be crumbling. It was quite sad.

The taxi driver wove adroitly through traffic. Occasionally he would "play a tune" on his horn. The horn was located below the dashboard to the right of the steering wheel. It had four buttons, sort of like those on a trumpet, and each made a different tone, allowing him to play the horn like a musical instrument. The people were dressed like Americans of modest means. They wore casual clothing for the most part-jeans or slacks or skirts, with collared short-sleeve shirts or t-shirts. No one was barefoot; everyone wore sneakers or shoes. The faces were of many shades, from what appeared to be Mediterranean features to African ones. Quite a few dogs roamed the streets. Half an hour later, Ransel indicated with a hand gesture that it was time to get out. I had been awaiting this moment with a fair degree of anxiety. I had been staring at the door for some time, and could not figure out where the handle was. Ransel noticed my confusion. He reached over me and opened the door. After the taxi drove away, he started laughing. "Your face!" he chuckled, mimicking an expressionless mask.

"You told me to be quiet so that they wouldn't know that I was a foreigner," I explained. Ransel led me into one of the many quaint but decaying buildings. He led me up three or four flights of stairs and into a three-bedroom apartment. It reminded me of the apartments dating from the 1930s and 1940s that I had once occupied in Santa Monica and Redondo Beach in southern California. But Ransel's apartment was much more run down than my old apartments. The walls were cracked and peeling, and the flooring worn. The only thing new was Ransel's laptop. He explained that it belonged to his employer. He said that he was officially unemployed and worked under the table ("a la izquierda," literally, "to the left") as a computer programmer. His wife, Anaidy, had an official job as a network administrator. That's how the couple had access to e-mail, unlike most Cubans. They lived with Anaidy's mother and grandmother. Ransel explained that such arrangements were the norm. No one can afford to buy a house in Cuba-which would be impossible anyway, since virtually no new houses are constructed. He said that some people subdivide their apartments and rent out rooms to very poor families. But that is illegal. Ann Marie, Ransel's mother-in-law, sent us to pick up some vegetables while she prepared lunch. I explained that I don't eat meat. She had been planning to cook some meat-a rarity, given the cost-in honor of my visit. I'm glad that I had a reason to make them save that luxury for themselves. We went to a rickety vegetable stand down the street and bought some lettuce and tomatoes. Then we returned and the lunch was ready. Ann Marie had made us rice and beans. I told her that I could not eat the lettuce or drink the water, since I'd been advised that they would upset my stomach. She peeled the tomatoes for me. She also peeled and cut some orange fruit.

I asked if it was papaya. Ransel laughed. He said that it was, but that I should be careful using that word. In Cuban slang, that is the word they use for vagina. I ate sparingly, fearing that I might get sick. (It turned out that I never got sick while in Cuba.) Afterwards, we each drank a small cup of very strong and sweet coffee. I thanked Ann Marie for the meal. But we exchanged few words. She spoke very little English, and my Spanish was very rusty. Then Ransel and I took another taxi back to Habana Vieja. We walked around quite a bit. It was a warm, sunny day. We talked about all sorts of things, and then drank some beers at a bar atop a building with a panoramic view of the city. The really interesting thing was the trip to the top of the building. It must have been just about the only building in Havana with an elevator. An old woman sitting on a stool worked as the elevator operator. We discussed many things. Ransel and Anaidy had applied to emigrate to Canada. They hoped to be granted a visa by the Canadian government by summer time. They also hoped that their own government would allow them to go after they receive the Canadian visas. Ransel was not very interested in politics, but he did express a dislike for Castro, and for the sham elections that were going on that very day in Cuba. (In typical Communist fashion, the voters were given no real choices on the ballot.) But Ransel's main reason for wanting to leave was economic. He explained that unless you have relatives abroad sending you dollars, it's almost impossible to survive in Cuba. Not much food is available via their ration books or for purchase in pesos. If a doctor gives you a prescription, it is of no use, since the pharmacies don't have most of the drugs that they prescribe. (If you're sick enough to go to the hospital, though, they usually can find the drugs you need.) I returned to the ship a bit before 5:00 p.m. to attend the briefing by US diplomats. Although the U.S. refuses to open diplomatic relations with Cuba, we maintain a de-facto embassy called the U.S. Interest Section. The students, faculty, and staff who attended the briefing were respectful, but most were opposed to the U.S. trade embargo and restrictions on travel to Cuba. The American diplomats defended those policies, claiming that the U.S. was trying to install democracy, the free market, and respect for human rights. Many people, including myself, suggested to them that this was hypocritical, given that we have good relations with China (not a democracy), Vietnam (which has a communist economic system), and human rights abusers like Saudi Arabia and Burma. My colleague, communications professor David Mould, quipped that he sympathized with the diplomats' responsibility to defend an indefensible policy, much as he'd once sympathized with diplomats from the former Soviet Union facing a similarly daunting task.

The next day I led a field trip to a local hospital and the main children's hospital in Havana. Basic health statistics in Cuba for things like life expectancy and infant mortality are roughly equivalent to those of the U.S. and other rich countries—and miles ahead of virtually every other country in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the hospital facilities were really run-down and dreary. In one room we watched personnel wrap in brown paper towels syringes that had been sterilized. In the U.S. and other rich countries, syringes are never re-used, for fear of causing infection. Health care in Cuba is a public good, not a commodity. All Cuban doctors—whether GPs or specialists—earn the same salary. The health care system focuses on primary care. There is a doctor's office every 100-150 meters in Havana, meaning that all families have a doctor within walking distance of where they live. The doctor lives above his/her office, and therefore is readily available in the event of an emergency. That evening Fidel Castro invited the participants in Semester at Sea to hear him speak at Havana University. He spoke eloquently and passionately. We were provided with earphones for simultaneous translation. I was amazed by the wide scope of Castro's knowledge. He touched on everything from evolutionary biology to globalization to relations with the US. Interestingly, he didn't say anything that sounded Marxist. His discussions of economics and politics—even that of international finance—were fairly accurate, and not that much different from what you'd expect from an American liberal. Castro was riveting. But after two hours straight, my attention began to wane, and I began to hope that the Cuban president was nearing the end of his speech. In fact, he went on for more than four hours. He stood the whole time and spoke without notes. I don't know how he did it. In fact, he did not seem the least bit fatigued. I think he'd have gone on for another four hours, had his aide not interrupted and thanked us for attending.

Everyone gave Castro a standing ovation, and while we were still standing he spoke for another fifteen minutes or so. I was extremely relieved when he finally let us escape. On the way out, we were given several books of propaganda. Then we traveled to a reception hall for a banquet. By the time I got to the tables of food, the Cuban students had devoured nearly everything. Many of them stuffed bags full of food, presumably to take home to their hungry families. The following day, I met Ransel and Anaidy. We had coffee in a café that had been frequented by Hemingway. Afterwards, I treated Ransel and Anaidy to lunch. For the three of us it cost only $14—including the rum. A real bargain for me, but a month's salary for Ransel. I'm glad I was able to take them out. That evening I went out for a walk on my own. I walked a great distance down a sidewalk along the water. I got some great photos of the ancient fortresses defending Havana harbor. I visited a museum in one of the fortresses showcasing artifacts from some of the many galleons and other ships salvaged from the harbor. The docent spoke perfect English and was very knowledgeable. After leaving the museum I walked some more. I met two young women. It was unusually cold and windy and they were trying to hitch a ride home. I spoke to them for a bit (with difficulty, since they spoke virtually no English) and then gave them each a dollar for a taxi home. One took a taxi but the other stayed and talked with me. We had a nice walk back to where my ship was. I learned that she was an 18-year-old college student studying to be a teacher of agriculture. She suggested that we take the ferry to the other side of the harbor where there was a huge statue of Jesus. We inquired about the schedule, and discovered that I would not be able to get back in time for the departure of my ship. By that point she was shivering from the cold. She indicated that she'd be willing to sleep with me if I'd give her enough money to buy a coat. She was quite cute and I'd be lying if I said that I was not tempted. But instead I bought her a beer and gave her my sweatshirt. She was quite pleased. She exclaimed something like, "que rico!" She gave me many kisses before I returned to the ship in time for departure. It is so sad that economic conditions are so harsh that college students are willing to trade sex for a warm coat. As I sailed away, I reflected on my visit to Cuba. I feel that the Cuban government has done a good job managing some things—notably health care and education—while doing a very bad job at others, such as human rights and economic policy. But most of all I am disappointed that that U.S. government continues to severely restrict the right of American companies to do business in Cuba and for American citizens to travel to Cuba. I believe that increased contact between our two countries will help to put an end to the hostility that has characterized U.S.-Cuban relations for the past half-century. After I returned to the United States, I kept in touch with Ransel and Anaidy. They finally received permission to emigrate, and arrived in Canada on August 8, 2003. They now live in Edmonton, Alberta. Ransel was able to find a job there as a software developer. Anaidy is still looking for an IT job. In the meantime, she is working at a cafeteria. Ransel recently wrote that they are very happy. They are living with a friend and have been able to send money to their extended family back in Cuba.

|

|

|

|

HOME | ABOUT DR. MILLER | POPULAR WORKS | SCHOLARLY WORKS | APPEARANCES | SEMESTER AT SEA | PHOTOS | CONTACT LEE |

|

|

|

Copyright ©

1998 - 2009 Lee Ryan Miller |